The Rain-Maker

by Phillip Challis

Published with permission May 18th, 2009

Morgan Booth looked up at a stretch of wide blue sky and waited for the miracle to happen. With the winds kicking up, little dust devils tumbled across the plains and scoured the land. Standing on the edge of town, Booth found himself surrounded by a sizable crowd of townsfolk. Their mood struck him as electric, like the static carried on dry winds that sometimes threw blue sparks off wire fences at night. That’s how it was with the people. They had an excited air about them. He could see a few had even gone so far as to throw coarse blankets down on the bare ground. Families tucked into their picnic dinners and children played in what used to be fertile soil now gone to lifeless powder.

This town was just the latest in a string of used up little communities he’d wandered into and out of again over the past few months. The past few summers had seen withered crops and wasted stock across much of the rolling countryside out west of the Big Muddy. In his gut Booth knew a lot of places wouldn’t make it past another winter. Even at the tender age of nineteen those towns tended to rattle him. They were too full of empty houses and empty fields that had dried up. Wheat, corn, cattle, and sometimes even the people went to dust and blew away. The town, he decided, felt like death and he avoided them whenever he could.

Today though, Booth saw the crowd of townsfolk out milling around and it raised his curiosity. Arriving on the coach an hour earlier, he’d made a point of finding what few stores lined the main street. There wasn’t much to see, and his hopes of finding work weren’t great. He walked from one end of the street to the other in the space of five minutes and that’s when he saw all the people. Ambling over, he quickly learned the reason for all the fuss. It was a man standing atop a wagon the likes of which Booth had never quite seen before.

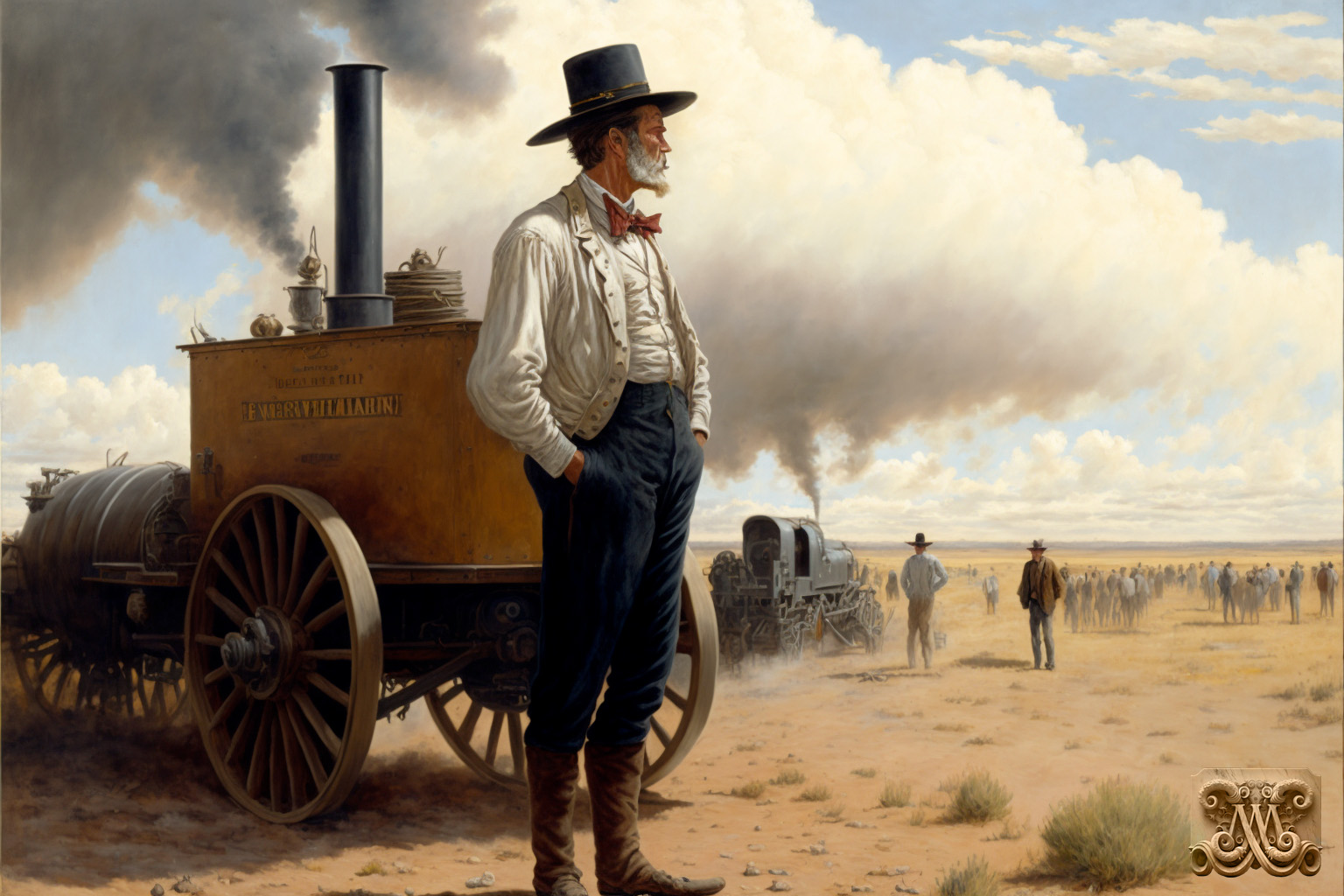

The handbill pasted across the wagon’s side proclaimed the man to be a rain-maker. The crazy looking collection of kettles, copper drums, and India-rubber tubes in his wagon was apparently a ‘patented gas generator’. Dressed as he was in dusty spats, a powder white frock coat, and matching white top hat of the old John Bull variety, he looked to be an eastern dandy, a snake oil man, or both.

Still, as ridiculous as he appeared, Booth did find the man’s machinery to be rather fascinating. The contraption mounted on the back of the old casket wagon hissed and rumbled as though it contained some sort of mythical beast. At intervals, little release valves sprung open and green vapor shot out. By the way they oohed and ahhed, the children seemed to think it was a regular Fourth-of-July.

Calling the crowd to attention, the rain-maker clapped his hands together. Then speaking in a clear, high voice, he said, “May I have your attention please? Attention please? I want to thank you good folk for coming out here on as God-awful a day as any I’ve seen. It warms my heart to know that so many of you have seen fit to place your faith in the science of man whereas too many have seen fit to throw their lot in with devilish powers or to give up entirely.”

Gesturing at the equipment in his wagon, he continued, “This lovely device, my friends, is the cornerstone of the artificial production of rain in our time! With it, I can create an exotic mixture of rare gases, leiden-jars, and wet batteries, all of which are neatly packed into the bodies of my patented paper-rockets. That’s right – paper-rockets. Why paper? Because it is light! Don’t you fret though, once the tubes have been stiffened by successive coats of varnish and paraffin, I can assure you that they are as tough and durable as an elephant’s knees.”

Turning, Booth saw the rockets staked out in a line just a little ways from the wagon. Each one stood about as tall as a man and all were attached to long wooden rods. The rain-maker paused for a moment and then spoke again. “These explosive devices, first pioneered by inscrutable Chinese artisans in the Far East, will be used to establish an electrical communion with the clouds above. The volatile gases contained within each of my rockets are charged with voltaic energy and, when properly exploded, will chill the very atmosphere resulting in condensation – rain, my friends! Rain! My miraculous generator here is large enough to produce some two hundred gallons of rain-making gas per hour, or the rough equivalent of twenty rockets.”

Booth shook his head in wonder. It was all a bit beyond him, but he had to admit that the fast talking rain-maker certainly had his patter down. From the looks of the people around him, the townsfolk were more than ready to buy his bill of goods.

Booth shook his head again and dug into his trouser pocket for the dollar coin he had. A hot meal seemed like a good idea, and he was about to walk away when someone asked him, “You here for the show, boy?”

Surprised by the question, he turned to see a wizened figure in tattered overalls and worn pair of old miner’s boots. Both man and boots were the dull color of road dust.

“Just passing through, mister” Booth answered slowly. “Though I must admit to some curiosity. You folks do this kind of thing regularly?” he said, thrusting a thumb in the general direction of the rain-maker.

The old man laughed, and it sounded to Booth like the braying of a water parched donkey. “That fool,” he cackled, “is always trying out some new fangled contraption or other. Got a powerful yearnin’ for the sciences.”

Tilting the brim of his hat up and scratching the side of his head with a ragged fingernail, Booth gave a kind of noncommittal grunt. Though there was no particular reason for it, he felt compelled to speak out on the rain-maker’s behalf. Maybe it was his own rebellious nature or maybe it was just his general sense of fair play. “Well now,” he said after a moment’s reflection, “I suppose a man is entitled to investigate the mysteries of the Lord’s creation as best as he sees fit. Don’t you think so?”

This elicited another burst of laughter. “Hoo-wah, yes-sirree! Best entertainment in town, boy. A couple of years back it were casting lightning bolts, if’n you can believe such a thing. Lightning!”

A little surprised at the revelation, Booth looked back at the rain-maker. “You don’t say? Well now, I suppose I have heard tell that Northern men can do such things.”

For a third time the old man laughed and the sound of it was setting Booth’s teeth on edge. “Oh now,” the old timer said once the guffaw’s subsided, “I’ve heard the same, son. The difference being, that feller over there won’t have no truck with witchcraft of any kind. It’s science or nothing at all with him. Damn fool’s as stubborn as they come.”

Though he’d rarely seen it for himself, Booth did know a little about the practice of witchcraft, or craft as it was more commonly known. And while it wasn’t as common in the States as it was up in the North, there were still plenty of practitioners and believers throughout the Union. Booth started reevaluating his first opinion of the rain-maker. Maybe, he thought, I was a just a little too quick to judge.

Leaving the old man behind, Booth crossed over to the wagon and, in an appreciative tone, said, “That is a fine rig you have there, sir.”

The rain-maker didn’t turn around. Rather, he spoke over his shoulder with bubbling excitement in his voice. “Why thank you, young man. It’s one of a kind and easily without peer or equal in these parts, but not for long. Oh no, mark my words, lad. Soon drought will be a thing of the past. My system will see to that!”

Booth nodded at the man’s back-side. “A fine sentiment, and it’s surely to your credit. My name is Morgan Booth by the way.”

At last, the man turned. After rubbing his hands with an oily rag he extended one in a polite greeting. “Hostlebeck, sir. Edwin P. Hostlebeck to be exact: amateur pluviculturalist, voltaic entrepreneur, and general man of the scientific arts. And what,” he said, grinning broadly, “would be your line, my young friend?”

Shrugging, Booth said, “Not much of anything just at present.”

Hostlebeck looked him up and down for a long moment and Booth imagined what the rain-maker saw. He figured it was what everyone seemed to see at first glance: a callow youth in a battered hat with an old army-gunbelt slung over his narrow hips. Combined with a forgettable face, he was easily overlooked in a crowd. Rarely, if ever, did anyone manage to see past Booth’s skin to the depths beneath. Hostlebeck though, must have caught some glimpse of those undercurrents, for he eventually said, “Have you ever worked as a cloud-buster, my young friend?”

Booth wasn’t entirely certain what a ‘cloud-buster’ was, but he figured it probably had something to do with the art of rain-making. “I cannot say I’ve had the pleasure, though I have handled rockets before.” The last he said with a gesture toward the ones Hostlebeck already had staked out in the pasture.

The rain-maker’s eyebrows shot up. “Is that so? May I inquire as to how you gained such experience? I beg your pardon, but you seem a trifle young to be acquainted with these devices.”

Nodding to show he was not offended by the question, Booth said, “I was a scout for Colonel Beatty. He had under him a troop of rocketeers at the Battle of Big Nemaha River right there at the end of the war.”

Hostlebeck nodded soberly. “Ah yes. Those would have been the older Congreve style of rockets. Primitive but revolutionary in their own right. Mine,” he said with a grand sweep of his arm, “are of a unique design, though in principle quite similar.”